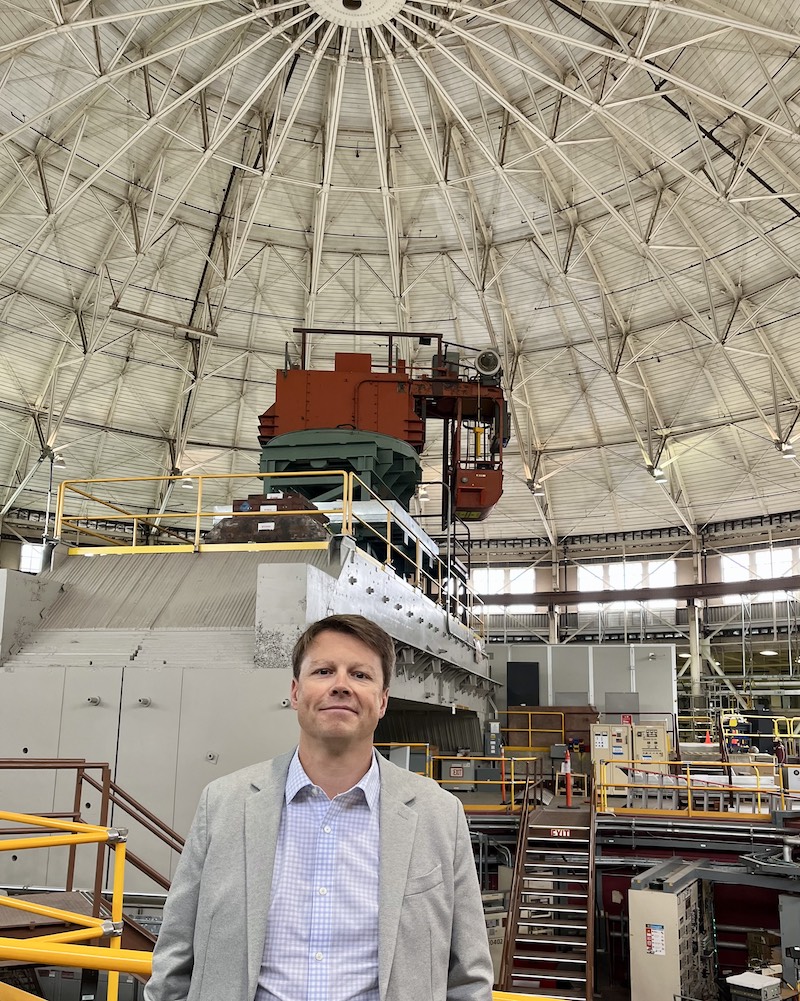

Simon Leemann’s job is to make sure the accelerator runs well—work that has taken him all over the world. Find out which languages he’s learned to speak as well as what gives him hope for the future.

Simon Leemann’s job is to make sure the accelerator runs well—work that has taken him all over the world. Find out which languages he’s learned to speak as well as what gives him hope for the future.

What does your role involve?

The Accelerator Operations and Development Group’s primary responsibility is to operate and develop the accelerator complex in the ALS, make sure it runs well, provides the required performance, and also to develop the facility such that we improve the beam performance.

What does it mean for the accelerator to run well?

There’s a couple of high-level figures that need to be met. For example, we want to see a constant current at 500 mA. The beam should have the expected position, angle, and dimensions. That’s for both shorter time scales, but also across a multiday user run. You don’t want any of these things to drift. You want the beam to be stored at those parameters without interruption; we don’t want to trip the accelerator off or lose the beam.

There’s a lot of things that connect to that. You want to inject into the storage ring efficiently. That means injections are quick, but still according to ALARA—as low as reasonably achievable—so that we’re not incurring unnecessary losses that create radiation background.

In top-off mode, we can inject without having to close the shutters or open the insertion-device gaps. Some experiments are sensitive to the perturbation from injection, but we can supply users with the signal telling them when we are about to do this, so they can gate their experiments.

Every once in a while when we’re dealing with an accelerator interruption, it feels to me like we’re not making enough progress, but then, I see an email from one of our beamline scientists saying, “We know you’re hard at work and we appreciate your effort.” There’s a lot of awareness of the complexity of the facility, and I don’t take that for granted.

What path led you to the ALS?

When I’d just gotten my bachelor’s in physics, I was kind of set on either high-energy particle physics or something closer to nuclear reactors, but because of the high-energy physics part, I got to do an internship at a lab that was just building up a brand new synchrotron. That was the Swiss Light Source, which had just gone into commissioning. I got interested in that, ended up doing my masters thesis there, and I really liked accelerators. I realized that I was more interested in the instruments than the high-energy physics, so I stuck around accelerator physics.

I dabbled a bit in free electron lasers during my grad work. When I finished my doctorate studies, there was a small accelerator lab in Sweden that was about to embark on the design of a new fourth-generation diffraction-limited storage ring, and that got me excited. I moved to Sweden and worked with them on that design for nine years. We built MAX IV, and after commissioning it, I figured this would be a good time for a change of scenery.

For a long time, I had wanted to come back to California, and I was aware of ALS-U. And so, when there was this opening in the ALS accelerator physics group, I figured this would be an exciting opportunity. That’s how I arrived here back in early 2017.

Did you grow up in California?

Yeah, I was born in Oakland and grew up in Walnut Creek. My dad was a nuclear physicist. He spent some time at CERN, so we moved to Europe and then came back to California. I actually knew the Lab because both my dad and my uncle worked here for a while.

What is it like to have lived in so many different places?

I’ve always enjoyed being where I was. I like languages, so traveling abroad is a good opportunity to learn new languages and have fun with that. If I learn a language, I try to speak to people in that language every chance I get. In Switzerland, I learned French and German; and then in Sweden, Swedish.

While I was in Sweden, my wife worked at a university in Holland, so we were commuting back and forth between Sweden and Holland. I didn’t learn proper Dutch, but I tried to pick up as much as I could. I would like to learn some Japanese. My wife grew up in Japan and she’s fluent in Japanese. We go to Japan every once in a while, and I would never dream of learning proper Japanese, including the kanji, but I’ve managed to learn a lot of words for food that I like. Through her, we have friends over there and it would be nice to be able to just have a very simple conversation in Japanese.

What do you like to do in your free time?

Aside from travel and learning languages, I play the violin. I like to hike and play softball.

How are you involved in inclusion, diversity, equity, and accountability (IDEA) efforts?

I was one of the at-large members of the ALS IDEA committee, and it was interesting to see the work firsthand. In accelerator physics, we have this problem that there’s not many women in the field. We do a lot at the Lab to improve our diversity, but our applicant pool often isn’t very diverse. I’m convinced that we need to create a more diverse pipeline to change that.

So, I’ve started teaching at the US Particle Accelerator School to get a younger and more diverse crowd interested in our field. And I’ve been a judge a couple times at the Contra Costa County science fair. The fifteen-year-olds there are doing a lot of awesome stuff. I try to encourage them to remain interested in these questions. These days a lot of people worry about the future. After coming back from the science fair, it’s hard to remain worried, because it’s tremendous to see what these kids are doing. If that’s the kind of potential that’s around in teenagers today, we’ll be just fine.