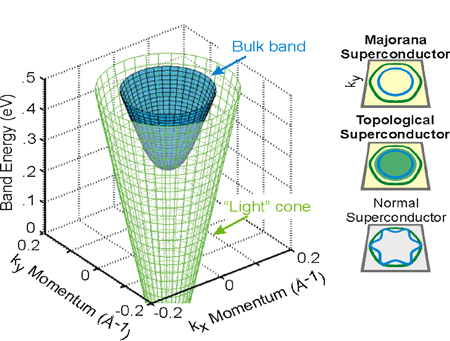

Three-dimensional topological insulators (TIs), discovered experimentally in 2007–2009 by a Princeton–ALS collaboration, are a promising platform for developing the next generation of electronics. Electrons within one nanometer of a TI’s surface move at high speeds in a “light-like” fashion. The quantum interactions that generate these electronic states cause individual electrons to be spin polarized even at room temperature and to strongly resist scattering from defects, naturally achieving some of the most desirable traits for computing components and next-generation “spintronics” technologies. More recent angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy (ARPES) studies performed at ALS Beamlines 10.0.1 and 12.0.1 by the same collaboration have paved a way for these novel material properties to be taken even further. Their studies showed that by doping the TI, bismuth selenide, with copper, it’s possible to make the topologically ordered electrons superconducting, dropping electrical resistance in the surface states all the way to zero.

It’s been broadly known that electrons at the surface of a TI move with no mass, in a way that’s mathematically equivalent to light (but 1000 times slower). In studies of copper-doped bismuth selenide, the researchers observed that electrons below the surface (in the bulk) are also “nearly-light-like” and, in a table-top setting, exhibit relativistic effects such as mass dilation that are usually associated with particles approaching the speed of light in a building-sized particle accelerator.

The connection between TI electrons and the physics of special relativity may at first seem like a mere mathematical oddity, but in fact it’s critical to understanding the behavior of superconducting electrons for technological applications. Because of the light-like, spin-locked behavior of the electrons at the surface, it’s impossible to describe superconducting behavior there using any standard theory. Based on this property and the number of points of quantum connectivity observed between different types of electrons in the material (a “topological” quantity), the researchers were able to establish that only two classes of theories can reasonably describe the superconducting behavior, each with novel physical properties that have been achieved in no other known material. Distinguishing between these theorized superconducting states of matter (“non-Abelian Majorana superconductor” and “topological superconductor”) will require future nano-engineering and quantum measurements.

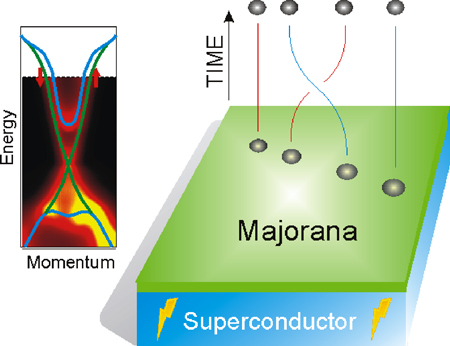

In addition to providing an incremental advance in material capabilities for technological applications, the unusual forms of superconductivity in TIs may in the future provide the basis for a whole new type of computer. If copper-doped bismuth selenide is the world’s first non-Abelian Majorana superconductor, as seems most likely from current research, electrons on its surface will readily form stable vortices (whirlpools) with an intrinsic quantum memory of their positions relative to other vortices. By manipulating the relative positions of vortices, it’s thought that the basic operations of quantum computing may be performed in a perturbation-resistant and fault-tolerant way. This property of quantum memory comes from the unusual laws of motion for topological electrons and is related to a type of fundamental particle called a Majorana fermion that has been theoretically postulated but does not appear to exist naturally in the universe. By creating new laws of electronic motion different from those that exist anywhere else in normal matter, TI superconductors can cause electronic vortices on their surface to become Majorana fermions.

The successful introduction of superconductivity into a TI is a long-anticipated achievement, and the resulting novel properties, such as relativistic electrons and quantum memory, will undoubtedly provide the basis for ongoing device-development projects. In a larger context, these results begin to give a richer perspective on the broad range of new physical phenomena that can be achieved with TIs and are only a first step in exploring their applications under a wide range of physical environments including magnetic fields, electric fields, nanoscale interfaces, and various quantum-interacting systems.

Contacts: Andrew Wray and M.Z. Hasan

Researchers: L.A. Wray (Princeton University and ALS); S.-Y. Xu, Y. Xia, Y.S. Hor, D. Qian, R.J. Cava, and M.Z. Hasan (Princeton University); A.V. Fedorov (ALS); and H. Lin and A. Bansil (Northeastern University).

Funding: U.S. Department of Energy (DOE), Office of Basic Energy Sciences (BES); National Science Foundation; and Alfred P. Sloan Foundation. Operation of the ALS is supported by DOE BES.

Publication: L.A. Wray, S.-Y. Xu, Y. Xia, Y.S. Hor, D. Qian, A.V. Fedorov, H. Lin, A. Bansil, R.J. Cava, and M.Z. Hasan, “Observation of topological order in a superconducting doped topological insulator,” Nat. Phys. 6, 855 (2010).

ALS SCIENCE HIGHLIGHT #220